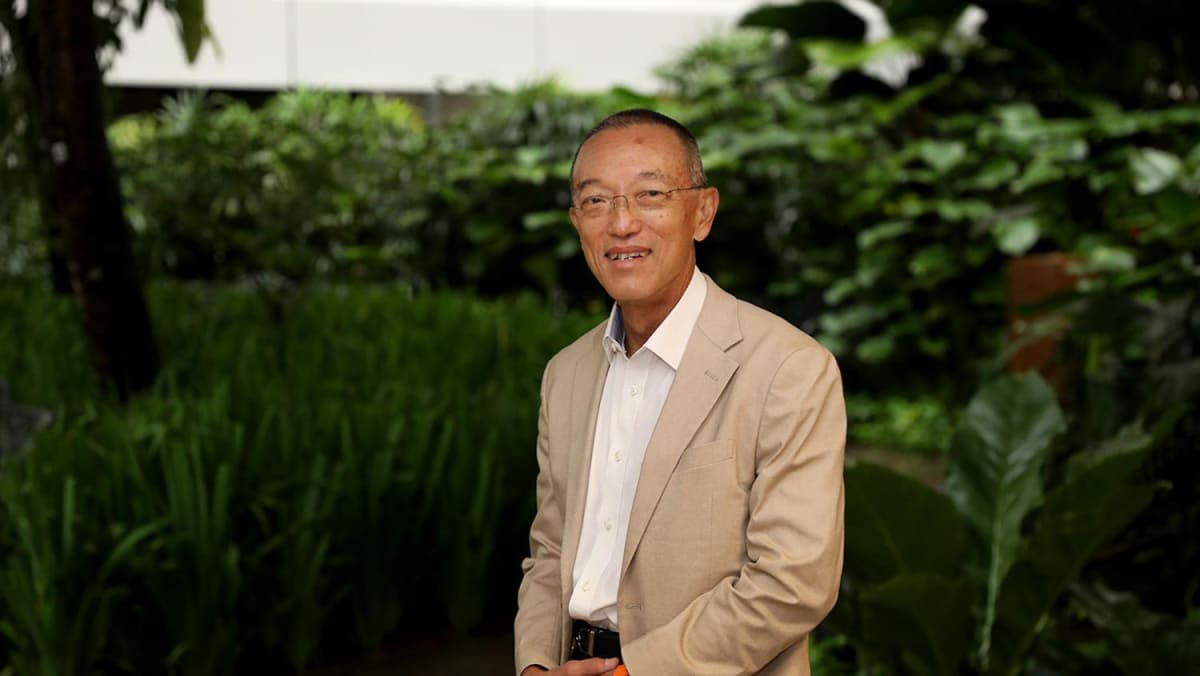

SINGAPORE — Having dedicated more than three decades of his career to the field of urology focused on prostate cancer, Professor Christopher Cheng was aware of the sobering possibility that he may eventually succumb to the very same disease he knows well as a specialist.

Despite experiencing symptoms such as waking up at night to pass urine and urinary retention years before his diagnosis, Prof Cheng had not thought that it was prostate cancer. Furthermore, a previous prostate-specific antigen (PSA) blood test done years back indicated that he was within the normal range.

“Also, I’ve had (urinary) symptoms for many years since I was a teenager. So my self-diagnosis was that it is very unlikely that it was cancer,” he said.

In 2017, a time in which Prof Cheng jokingly referred to as “all hell break loose days” when he and his team were up to their neck preparing for the opening of Sengkang General Hospital, a prostate examination revealed a suspicious nodule and likely prostate cancer.

He was the chief executive officer of the new hospital then.

The finding was unexpected because he had attributed his urinary symptoms to an enlarged prostate, a benign condition, and had scheduled surgery during the year-end festive break in 2017 to relieve the symptoms.

He recalled receiving results of his PSA blood test while in the midst of a meeting. It was at a “shockingly high” level of 17.8 nanograms per decilitre (ng/dL), which he knew spelled bad news for anyone with prostate cancer.

The PSA is a substance produced by the prostate, which is the small gland that sits below the bladder in males.

While a small amount is normal, men with prostate cancer tend to have higher levels of PSA in the blood. Other conditions, such as an enlarged prostate, may also raise PSA levels.

“In some (overseas) centres, if you have prostate cancer with a PSA of 17, the top surgeons will not operate on you because it would tarnish their results,” Prof Cheng said.

In his book, he explained that some famous centres do not offer potentially curative treatment to patients with a PSA of more than 10, because poor outcomes may affect their reputations unfavourably.

Prof Cheng has since gone through many episodes of emotional ups and downs while waiting for his PSA test results.

“After treatment, every blood test becomes that lying-in-wait to know what the result is,” he said.

“As someone who is supposed to be an expert and knowledgeable in this, I know about all the bad things that can happen.

“It’s either relief or disappointment, multiple (times of) fear, anxiety, anticipation.

His experience has changed the way he informs patients of their progress. Previously, for patients with a good PSA test result, he would print out the result and congratulate them.

“Now I do an extra step,” he said. “If I see an undetectable PSA after surgery, I give the patient a hug and I may have tears in my eyes. Because I think they are free.”

While being on the receiving end of cancer treatment has given him better insights into what his patients go through and greater empathy, Prof Cheng pointed out that no one can claim to truly walk in another person’s shoes.

Even when experiences may seem similar, every individual would have a different perception of their lived experience.

“After the surgery and treatment, I also thought that, okay, I’ve been through all these complications, all these experiences, I can show my patients the (surgical) scars and tell them ‘I know how you feel’.

“But no, even after you’ve been through it, everybody who goes through the same journey takes away different things,” he said, adding that this is why it is important to retain humility and openness, and not be judgemental towards others.

‘COMPASSION FATIGUE OVERRATED’

During the interview, Prof Cheng brought up the topic of compassion, which is also a recurring theme in his book.

Experiencing what it is like to be a patient has made him more mindful of the importance of connecting with patients at a deeper “heart” level as a medical practitioner.

This is something he hopes that young doctors would be more aware of and put into practice as well, even when facing seemingly challenging patients.

His personal take on “compassion fatigue” — which some may consider controversial — is that it is “overrated”.

“I think that in giving compassion and care, you receive double the amount,” he said in the video interview.

The term “compassion fatigue” describes the physical, emotional and psychological impact resulting from repeated exposure to traumatised individuals or adverse traumatic events.

It is commonly reported among people who work in a helping profession, such as in healthcare, and can desensitise healthcare professionals to the needs of their patients, causing them to lack empathy.

Prof Cheng’s take is that when it is a good day’s worth of work, “you go home dead tired but you’ve had a fulfilling day”.

“If our heart is true, I don’t think that compassion, by itself, can lead to fatigue.”

Recounting a talk he gave earlier this year on compassion for a group of first-year medical students, Prof Cheng told TODAY that he extended an offer to the students to visit his clinic.

“I said, when you guys are tired and burned out, come to my clinic and connect with the patients. What burnout is there when you can connect with a human being?

“When you touch them at the ‘heart’ level, and you are authentic (and) genuine, people know.”

ON HAVING A ‘GOOD DEATH’

As a doctor who has seen patients at death’s door, Prof Cheng came to the realisation that death is an experience that everyone faces alone.

“However rich, however powerful (they) are, they’ve all had to face death eventually. They all have to let go,” he said.

The difference, however, lies in how one faces death.

Once, he asked a patient whose disease had worsened how he was coping, to which he replied, “I have no complaint. I can eat, I can urinate, I can pass motion. I’m okay”.

“I thought, wow, this was really contentment with very little. And he had no angst.”

Then, there are also patients who are full of anger and resentment, and are unable to reach “peaceful acceptance”.

To Prof Cheng, the concept of a “good” death is similar to that of happiness: It is not something that one can achieve by simply checking off a list.

“You can’t go out, do online shopping and buy happiness. You can’t go through a checklist and say, ‘Okay, I’ve done this, I’ve settled my will, I’m going to have a good death’,” he said.

“But I know what’s not a good death — being full of anger, rejection and loneliness, etc.

“I think the path to a near-good death is to try to remove as many obstacles, as much clinging (to attachments), disappointments and resolve as many regrets that you can.”

Prof Cheng said that after his cancer recurred, the oncologist proposed an “all-in, kitchen sink” approach, which meant giving maximum treatment available.

“I opted out of it and decided to have very focal, localised (treatment). After a long, long discussion, I didn’t want an all-out treatment that would most likely give me many side effects,” he added.

“People ask me, ‘So, how are you?’, they are concerned. (I tell them) I’m as good as could be, nothing to panic.

“I’ve everything I need to be happy, and more. I don’t think that being at the receiving end of the kitchen sink is going to make me any happier.”

Prof Cheng is considering writing “season two” of his experience but expressed some hesitation over it.

“Part of the reason is because one man’s experience is a drop in the ocean. When you write something, you need to basically present a scientific account because people will hang on to those little things.”

For now, he is doubling up his efforts to live life to the fullest, and to be fully present in all that he does.

“No more postponing meeting the people I really like to catch up with; no more procrastinating on things I would like to complete. Every task is taken as though it is the last chance,” he said.

“For the first time, I have a cycling coach and I am winning races for the first time in my life. My paintings are now exhibited, good enough to be sold for charity. Most of all, I make peace with things I accept as being beyond me.

“Every moment is precious. Every encounter is ‘here and now’, like this (interview), at 100 per cent attention,” he added.

“And I’m not in a hurry to go anywhere.”

The Lien Foundation’s Doctors’ Die-logues video series can be found online.